The Family Giving Lifecycle: Governance Primer

Tool

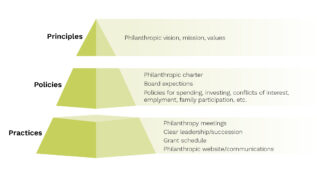

Governance is a framework in which you name how decisions will get made in your philanthropy and by whom. This primer will help you demystify governance, think through whom you would like to join you, and how you will make decisions as a group.