Effective Family Philanthropy: The Sobrato Family

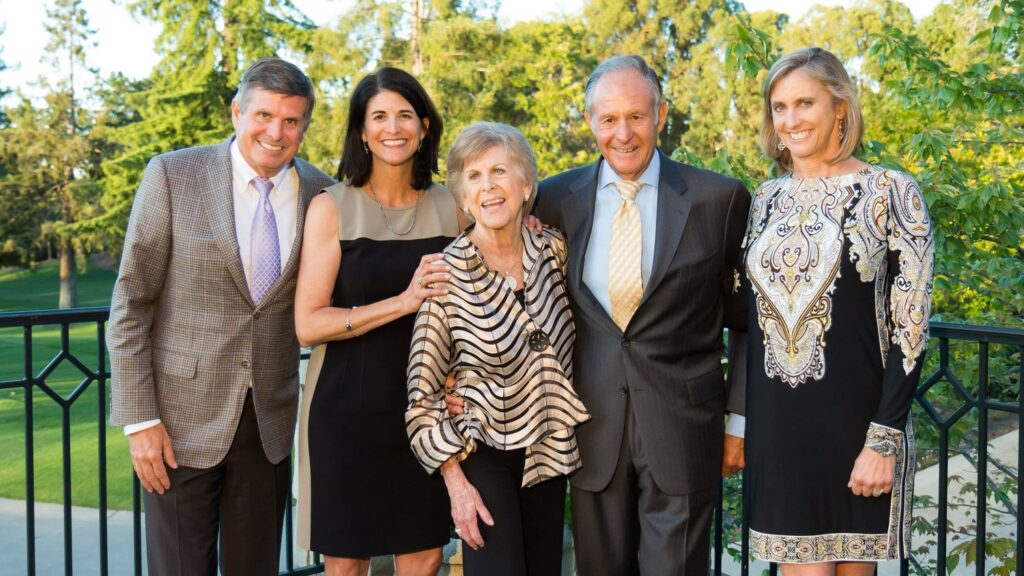

From Left To Right: John Michael Sobrato, Lisa Sobrato Sonsini, Susan Sobrato, John A. Sobrato, and Sheri Sobrato Brisson.

The Personal and the Collective: How Three Generations of the Sobrato Family Give

The Sobrato Organization in Silicon Valley has developed more than 21 million square feet of office space, R&D and multi-family projects since the 1960s. Today, the company’s real estate portfolio includes over 7.5 million square feet of office space in Northern California, with tenants like Netflix, Airbnb and Amazon—along with some 6,700 apartments.

The developer boomed as Silicon Valley came of age and the family behind it is worth around $6 billion as of this writing.

Patriarch John A. Sobrato, 82, began his real estate career in the late 1950s by selling homes in Palo Alto while attending Santa Clara University. Sobrato launched Midtown Realty, selling residential properties in the burgeoning suburbs. In 1974, he sold his interest in the company, moved to Cupertino, and concentrated on developing industrial properties for the emerging high tech industry.

The Sobrato Organization was born.

Today, John A. Sobrato is chairman emeritus of the organization, while his son, John M. Sobrato, serves as chairman. The Sobrato Family Foundation, meanwhile, was launched back in 1996. Family giving has since grown under the umbrella of Sobrato Philanthropies—which includes Sobrato Family Foundation, as well as other entities—holding nearly $920 million in assets and giving $161 million in the 2020 fiscal year.

Sobrato Philanthropies’ mission is to partner with organizations to meet immediate needs in the community, address systemic barriers, and pursue social justice. Count the Sobratos as another billionaire family whose philanthropic interests have evolved to focus on racial equity, as well as other causes like climate change and democracy, which have come under unprecedented threat. But how did the family’s giving end up at this point?

We recently connected with three generations of the Sobrato family to find out how giving has changed from those early days, why several family members signed the Giving Pledge, how the different interests of the family are balanced, and how the family views its philanthropic legacy in the Bay Area and beyond.

Getting started

Son of John Massimo Sobrato of Suza, Italy and Ann Ainardi of Washington State, John A. Sobrato grew up in the Bay Area. John Massimo owned a large restaurant where Sobrato worked during the summers. He recalls seeing his father giving cash to employees who were struggling. Ann, meanwhile, volunteered as a pink lady at Stanford Hospital and also worked at the food kitchen at St. Anthony’s Church, in a low-income neighborhood.

Years later, as the Sobrato Organization soared, John Sobrato says the family was fielding hundreds of phone calls and letters for donations throughout the year.

“It was like Christmas time, but 12 months of the year. And it just started to become overwhelming,” he explains.

The family decided that this was the moment to professionalize their giving. Sobrato’s daughter Lisa Sobrato Sonsini was instrumental in getting the family’s foundation off the ground. A young associate at the time at Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, Lisa found a lot of joy in pro bono work and convinced the family to formally launch the Sobrato Family Foundation in 1996. The Sobratos also hired Diane Parnes, the Sobrato Family Foundation’s inaugural executive director, who started creating giving categories so that the family could filter requests.

In those early years, Sobrato’s daughters Lisa and Sheri were doing all of the site visits for the foundation. But when Lisa and Sheri started their families, additional staff were hired. John Sobrato believes that it’s important that they sit down with each grantee and learn about their mission. “You really need face-to-face meetings for that,” he says.

The family initially focused their giving on the communities where they made their real estate fortune, in Silicon Valley. Sobrato notes that, especially back then, a lot of other philanthropists in Silicon Valley didn’t necessarily focus on the region, pointing out that about 60% of those working in technology in the area are foreign-born.

“There wasn’t anybody focusing on the needs of Silicon Valley. That’s why we did it. My wife Susan and I were both born in Northern California. We went to school here. Our roots are here. So, too, for all of our children,” Sobrato says.

Education and healthcare

John A. Sobrato himself has mainly been drawn to education and healthcare in his giving. “I think education is the surest way for an individual to work himself out of poverty.”

Several Sobrato family members, including John A. Sobrato himself, were educated at Santa Clara University, a Jesuit institution in the heart of Silicon Valley. It should be no surprise that Sobrato remembers the institution fondly, juggling his first real estate business with his studies at the university. Sobrato was invited to join the board of regents around a half-century ago, using his real estate background to broker a campus relocation.

Later, John and his wife Susan Sobrato were major donors to Sobrato Residence Hall. They then donated $20 million to build the University’s Harrington Learning Commons, Sobrato Technology Center, and Orradre Library, completed in 2008. And in what Sobrato calls their “grand finale,” the couple donated $100 million to launch the Sobrato Campus for Discovery and Innovation, which just opened in late 2021. Sobrato cut the ribbon alongside fellow Santa Clara alumnus California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

On the healthcare front, philanthropy is driven in part by the couple’s own experiences, as their daughter Sheri battled a brain tumor when she was in her early 20s. Susan, in particular, has been drawn to health causes, as well as advocating for women who have suffered abuse.

John and Susan Sobrato made the cornerstone $20 million pledge to Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital for the Sobrato Pavilion, and created similar spaces at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, and at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose.

“We believe that good healthcare is a God-given right. All these institutions offer high-quality care regardless of your ability to pay. That was very important to us,” John Sobrato says.

Bringing in the family

All the way back in the 1970s, when Sobrato and his former business partner Carl Berg split up their properties, Sobrato’s lawyer suggested that it was a good idea to bring in his children as business partners. Today, John A. Sobrato owns only 40% of his company, and his children and grandchildren own about 60%. And because the whole family is in business together, he also believes that the whole family should be in philanthropy together.

The family’s philanthropy has evolved over time, with second- and third-generation family members bringing their own interests and perspectives to the table. Sobrato Philanthropies includes the Sobrato Family Foundation, but also several donor-advised funds via Silicon Valley Community Foundation so family members and couples can engage in more personal giving.

“One of the interesting things about Sobrato Philanthropies is that it is really a platform that both supports the family’s collective giving, things that we’re doing together, as well as our individual giving. And we set up our philanthropic resources to support both,” John Michael Sobrato, 60, John and Susan’s son, explains.

John Michael and his wife Timi have two main priorities: climate change and democracy. John Michael pins the formation of their foundation all the way back in 1996 as the moment when the family really shifted from being reactive in their giving to focusing on strategically solving problems. He says Sobrato philanthropy is about 80% strategic today.

Toward sustainability

In the broad area of climate change philanthropy, John Michael and Timi Sobrato have decided to focus on mitigating the effect of industrial agriculture on climate change by trying to build a more humane and sustainable food system. Longtime vegetarian and environmental advocate Timi Sobrato grew up competing in the hunter/jumper equestrian circuit in Southern California, and as an adult, trained thoroughbreds with Ian Jory Racing Stables.

“I’m not a vegetarian. Timi is. We have one of each of us. We’ve been trying to eat fewer animals and promoting a healthier, vegetarian or vegan lifestyle for decades,” John Michael explains.

Vegans and vegetarians still make up well under 10% of the population in the United States, John Michael says, so their theory of change revolves around coming up with tasty, accessible and affordable alternative protein options that mimic culturally familiar foods. Besides sustainability, Timi mentions that their work also intersects with issues of health, citing overuse of antibiotics in industrial farming. And John Michael points to the global food security impact of eating meat, as a plant-based diet is far more efficient.

Researchers have found that animal agriculture is responsible for around 15% of GHG emissions, and the couple do not discount the enormous impact of transportation and power generation, for example. But as philanthropists, they want to focus on this often overlooked issue.

“We can change what we can eat. And we can make it easier to change what we eat. This is our focus. It is very tractable. Impossible and Beyond [two new plant-based meat substitutes], that’s ground beef, and really just the tip of the iceberg. The iceberg is pretty much every animal and dairy product we eat being replaced with a plant-based alternative,” John Michael says.

John Michael and son Jeff Sobrato also engage in impact investing in this area and are encouraging young companies to invest in alternative protein. Meanwhile, they are also doing early work on the policy front with a 501(c)(4) called Food Solutions Action.

“When the cheapest burger, rather than the most expensive burger, is the one made out of plants, that’s when there really could be a major change,” John Michael adds.

Prioritizing democracy

John Michael and Timi Sobrato also prioritize democracy work in their giving, recognizing that without a functioning federal government, none of the good policies that they believe in can become law.

“We’re trying to get our representatives to act in the best interests of the country, rather than focusing on staying in power at any cost, which is what it’s looking like now,” Timi says.

The couple believes the current incentives are wrong, and their main focus is on changing the way Americans elect their members of Congress. They’ve been supportive of ranked-choice voting, and moving away from partisan primaries to a “final five” open primary, in which all eligible voters can vote for anyone who wants to run for either House or Senate seats.

“You have five finishers. So you create competition. And more importantly, you eliminate the fear of getting primaried and not reelected,” John Michael explains.

“Hopefully, because you have to appeal more to the middle, we’ll get less-ideological candidates that have the ability to reach across the aisle without fear of losing their job,” John Michael adds, mentioning that the couple focuses on pulling 501(c)(4) levers on this front.

Two generations of pledgers

John A. and Susan Sobrato, along with John Michael and Timi Sobrato, are the first multi-generational signatories of the Giving Pledge, both signing in 2018. John A. Sobrato tells me that he received a personal call from Warren Buffett, who gave him the pitch. Sobrato initially thought it was his old business partner Carl Berg, known for such jokes. But it was indeed the Oracle of Omaha.

Sobrato had already decided a few years prior that he would direct 100% of his wealth to charity upon his death. But Buffett insisted that Sobrato still sign and attend meetings. Up until COVID, Sobrato says pledgers had an annual in-person meeting. When he signed, there were about 100 pledgers. Now there are upwards of 250.

“They bring all the pledgers together, put on seminars, and you kind of learn from other folks what their interests are. And you also hear a lot of the probing questions of what philanthropists struggle with. For instance, spend-down,” Sobrato explained.

John Michael also spoke to the value of the Giving Pledge community as a learning journey. “It’s not as if they bring in a bunch of consultants on a panel. Really, it’s the pledgers themselves sharing their own experiences. How they staffed up. How they think about their obligations. And everyone is in a different stage of the process. I think that was the goal of Gates and Buffett. To help get their fellow philanthropists unstuck,” he says.

Timi mentioned Cari Tuna and Dustin Moskovitz as being particularly helpful in guiding their philanthropy, as well as Laura and John Arnold.

These days, John Michael and Timi Sobrato are focused on giving with more urgency and embracing giving while living. John Michael says that strategic philanthropy is moving away from the Ford/Rockefeller model of perpetual foundations.

“The technology age has produced way more wealth than the industrial age. So when you do a spend-down, there will be others to take your place that will provide that ongoing support,” he says.

The next generation

John Michael and Timi Sobrato’s two sons, John Matthew and Jeff Sobrato, in their 30s, are among the third generation of Sobrato philanthropists. Also in the mix are a set of cousins in their late teens and 20s, going through college, and another set that are just entering high school.

“For those other sets of cousins, they are very new to this, and for the first time, exploring some of their interests. It’s really on my brother and I to set the precedent that the younger generations are going to follow,” John Matthew says.

Another Sobrato graduate of Santa Clara University, John Matthew spent a decade working on the east side of San Jose, including six years as a high school history teacher. A product of Catholic schools and a Jesuit education—which emphasized the importance of social justice—he wanted to work within schools in the Bay so that he could give back directly.

“I see education as a critical lever in bringing about a more just society. I really wanted to go and work within schools in my community that were very different from the more affluent schools that I had the privilege of going to,” John Matthew explains, calling the experiences life-changing.

John Matthew later put on his administrator hat as an assistant principal, which further allowed him to see concretely the vast disparity in opportunities—sometimes just 15 minutes away from the communities he knew well.

“There were just so many things that I had never considered before, because my own privilege, my identity and my network largely insulated me from ever having to confront those challenges,” John Matthew says.

Around the same time, in a refrain we’ve heard from other next generation philanthropists, John Matthew found himself moved to act during the pandemic, especially on the heels of the murder of George Floyd and subsequent protests. He felt this was the moment when he needed to step up and make a formal transition to philanthropy, and move beyond his work in the classroom.

A social justice lens

For the past year or so, John Matthew has been, as he describes it, plugging himself into the different parts of Sobrato Philanthropies. It’s worth emphasizing that he has never been involved with the family business, a conscious decision on his part. But on the charitable front, he’s been learning on the go, focusing on Sobrato’s English Learners (EL) program and other educational efforts.

Sobrato’s EL program builds on the Sobrato Early Academic Learning (SEAL) model that provides a research-based foundation for English learners in preschool through third grade across California. The Golden State itself has made significant policy changes that allow for greater equity for English learners, including Proposition 58 in 2016, which repealed bilingual education restrictions enacted by Proposition 227 in the late 1990s.

John Matthew has been heavily involved with SEAL since he joined Sobrato Philanthropies. When the organization spun off into its own nonprofit, the family tapped John Matthew to become board chair and guide its next chapter.

“I’m just a big believer, because English learners are really the future of California. I think something like 60% of students under the age of five are dual-language learners, but historically, they’ve been an afterthought,” he explains. SEAL works through multiple rungs of the educational system, including teachers, administrators, policy tables and educational coalitions.

Overall, John Matthew believes education philanthropy is starting to do a better job at listening to stakeholders. For instance, in post-secondary education, there was a time when philanthropy only thought about upfront costs like tuition, which was addressed with scholarships. But now, philanthropy is starting to listen to students, including their need for mentorship, help with enrollment in classes, and for affordable books and food.

As vice chair of the Sobrato Family Foundation board, John Matthew has also been thinking about ways he can leverage his unique position within the family to bring these equity-minded perspectives to bear. He says he’s been doing a lot of learning and reading over the past year and wants to help the family to see and do things differently.

“Especially for someone like me, it’s clear that this is the role I need to play. No one has more power or influence than those who you are closest to. So I really need to start with focusing on my family. I started as a thought partner and an advisor. And now I’m really thinking about my role within the governance structure,” he says.

Jeff Sobrato also backs systemic change and social justice in his emerging giving. The two brothers tend to think about the world in similar ways, John Matthew told me. They are only 18 months apart, after all, went to the same schools, and shared the same room until they went away to college. Jeff has a passion for storytelling and film, however, and takes more of a narrative change approach. He is a producer of the 2018 Netflix film “A Private War,” about war correspondent Marie Colvin.

“There’s so many harmful narratives that exist within American life that reinforce and perpetuate these inequities. We have to figure out ways to kind of change the conversation and change the story,” John Matthew says.

“It all comes down to values”

As they become adults, all Sobrato bloodline family members can join the Sobrato Philanthropies board. Through the separate Family Philanthropy Council, spouses and bloodline family members come together to set the family’s philanthropic priorities.

John Michael Sobrato says they are going through an evolution of sorts, where family members will definitely still have an opportunity to serve on the board, but it won’t be in perpetuity. Four non-family members currently serve on the board, and John Michael really wants to open it up to outside perspectives and increase diversity so that they reflect the communities they serve.

Sobrato Philanthropies currently operates with 13 board members, but wants to institute term limits to limit this size. The board meets quarterly. As Sobrato Philanthropies has evolved, giving upwards of $100 million annually, John Michael says that rather than focusing on individual grants, conversation focuses more on an overall theory of change.

“We’re maturing. And really want to spend our time on strategy, how we’re going to measure outcomes, and what we’re learning,” he explains, adding that, “we have a very capable staff and committees to handle these other things.”

In terms of how these many different voices are weighed across this multi-generational endeavor, John Matthew says it all comes down to aligned values. “If it’s an issue area, strategy or an approach that may be unfamiliar, it’s all about speaking about it in terms of what our family values and helping them see how doing a certain thing can help us live into those values more fully,” he explains.

Building a philanthropic legacy

Catherine Crystal Foster, a Bay Area veteran social impact leader, works to close the disconnect between Silicon Valley dollars and the great need within Bay Area communities. The Sobratos were backers of Magnify Community, a time-limited philanthropic innovation lab, created to catalyze more local philanthropy, that Foster led until it wound down operations last fall.

She has seen the evolution of the Sobrato family’s giving firsthand, going back to her days working for the Peninsula College Fund and even earlier. “For many years, they were giving a lot of capacity-building funding, which was great, and giving general operating support. They really went deep on a local level,” Foster says.

One more compelling example of this hyper-local work is Sobrato Philanthropies’ four Sobrato Centers for Nonprofits, which converted commercial office properties into multi-tenant nonprofit centers. In fact, Peninsula College Fund is a Sobrato Center tenant. The roots of this work began when John Sobrato’s mother Ann built a multi-tenant property in Milpitas. When she passed away, she left her 50% interest in that asset to the family’s foundation. John A. Sobrato then bought out the other owner.

Even before the Silicon Valley prices of today, the Sobratos observed that office space rents were particularly hard on nonprofits. So Sobrato replaced paying tenants with nonprofit tenants who could use the property rent-free.

That initial space always had a waiting list, which ultimately led to the creation of three more Sobrato Centers, the newest of which opened in Palo Alto in 2021 and will have a 12 nonprofit capacity. All told, the centers can hold around 78 nonprofits.

Patriarch John A. Sobrato is proud of the family’s work through the years in Silicon Valley, but also that this work has expanded beyond its original locus. When I asked him about the family’s legacy, he pivoted to honoring the work of the foundation’s staff, starting with inaugural Executive Director Diane Parnes, and now with Sobrato Philanthropies President Sandy Herz.

“Sandy’s charge when we hired her was, let’s grow this thing while we’re alive rather than wait until I’m deceased. Or my children are deceased. Let’s do more today. So we’ve quadrupled our giving budget. So, you know, we’ll see. Stay tuned,” he says.