How Your Foundation’s Records Can Measure Impact, Manage Risk, and Promote Transparency

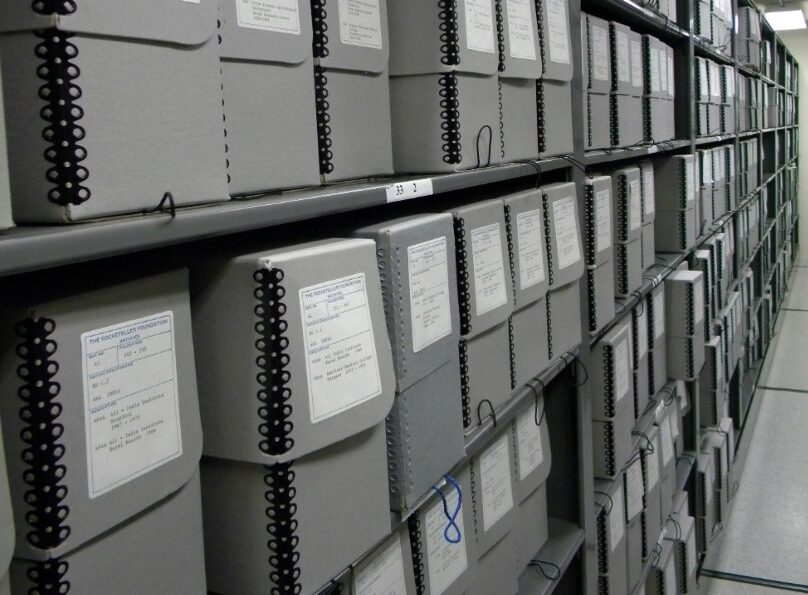

The vault at the Rockefeller Archive Center

Your foundation’s information is an asset and managing that information with record and knowledge management—and perhaps an archives program—can help you preserve your family’s legacy, ensure that you’re complying with legal requirements, make your impact clearer, and help you live into values like accountability and transparency. While foundations have different goals that may inform their individual approach to information governance, Bob Clark argues that there are critical concepts that all foundations should consider.

Do you wish you had access to better information and data with which to measure your impact?

If you had to respond to a legal request for records about your activities, do you know with certainty where that information is located and who is responsible for it?

How will the legacies of your programs and grantees—and of your family—be told five, twenty five, and fifty years from now, and who will do the telling?

In my role as the director of archives at the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), I often ask these questions of curious foundation leaders who want to know why their organizational records matter in the first place. In our experience, the answers can be found through information governance, the term used to describe the policies, procedures, and systems used to manage the records and data your organization has created and is creating daily. A foundation’s archives are the ultimate output of information governance.

The RAC was established in 1974 to collect, manage, and preserve philanthropic records, inspire critical analysis, and contribute knowledge for the public good. Our vast holdings of philanthropic records include large institutional philanthropies, as well as family and limited life foundations like the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Leon Levy Foundation, the Rockefeller Family Fund, and the Albert Kunstadter Family Foundation.

It’s no coincidence that the RAC was founded in the wake of the 1969 Tax Reform Act, which established many of the legal requirements for private foundations, with the goal of promoting greater transparency and understanding of the work and impact of foundations.

Critical Concepts in Information Governance

In conversations with foundations that are just beginning their information governance journeys, I often discuss these core concepts:

- Information is an asset: The information your organization creates is an asset just like your endowment and investment portfolio, the building you occupy, and the human capital that makes up your staff. Managing your information assets responsibly is an ongoing commitment.

- Articulate your goals: Any successful information governance program requires that you first develop goals, such as establishing an internal knowledge repository for learning and evaluation purposes, celebrating an anniversary, reducing your digital storage footprint, meeting legal compliance requirements, or providing for a public-facing archival collection.

- Develop a records retention policy and retention schedule: We always recommend that organizations develop an institutional records retention policy and retention schedule. Doing so will compel you to survey your records landscape, identify which systems are being used for what purposes, and articulate how long certain categories of records are to be saved. A comprehensive retention policy and schedule are the foundation for any successful information governance program and for the creation of an archive. And in challenging legal environments, having a fully implemented retention policy and schedule can be your best friend when it comes to managing risk by creating a clearly articulated framework for why you retain some records but not others.

- Focus on content, not format: Don’t get caught up in the formats of the records but evaluate them based on content instead. Related content might be found in your paper files, email system, grants management system, payment system, and shared drive, and they may be physical documents, emails, PDFs, Word and Excel documents, or data sets. Typical records categories include grant records, board of trustees records, communications records, and program and policy records. You can say where such records are located as part of the process, but “Bob’s filing cabinet,” “emails,” or “SharePoint files” are not records categories.

- It’s a program, not a project: Too many organizations think that information governance is about cleaning up past records issues. But unless you develop an ongoing organization wide program in support of information governance, there will always be another mess to clean up. Successful information governance requires having someone who interacts daily with staff about how they’re using systems, who participates in systems upgrades and migrations, who follows through on records dispositions under the retention policy and schedule, and who advocates for the work up and down the organizational chart.

- AI can augment but not replace information governance: We hear a lot about AI or machine learning these days. But machine learning is only as good as the data it’s learning from. A strong information governance program with clearly articulated goals, policies, and practices will be able to use the power and potential of AI to further analyze and learn from the records that have been identified and organized through information governance.

- Build it into your organizational culture: For any information governance program to be successful, buy-in from an organization’s leadership and stakeholders is critical. You need to clearly articulate how information governance is consistent with your organizational mission and values around transparency, equity, and accountability. Consistent messaging about its importance, whether limited to just records management or expanded to include knowledge management and archives, ensures that everyone in the organization is part of the solution.

- Consider family legacy: When we speak with family foundations, we often hear the refrain from founders and their families that “it’s not about us; it’s about the work.” What’s important to accept, though, is that the work is happening because of the vision behind marshaling those resources for the public good. Your family and the foundation are inextricably intertwined. The story of the organization can’t be told without also telling your story. Committing to an archive program can be a very personal and emotional endeavor. That’s an expected part of the process and having your foundation’s story archived will preserve the values and legacy for future generations to steward.

- If your foundation’s lifespan is limited, start early: If your organization is a limited-life foundation, start thinking about information governance—and especially the value of placing your records at an archival repository—as early as possible. If you wait until one or two years before your spend-down date, you will have lost staff and institutional knowledge. It also takes time to negotiate the terms for a deposit of records with an archive and to facilitate the transfer of records. Waiting too long means you may run out of time and that the stories of your foundation, its grantees, and its staff are lost to history.

Getting Started

We know that embarking on an information governance program can be daunting. But there are resources you can consult as you begin to develop the strategies and goals that will lead you to success.

And remember, one size does not fit all. Your information governance program does not need to look like that of any other organization. It needs to work for you.

The Advancing Foundation Archives: Advocacy, Strategies and Solutions report serves as a guide to best practices for records management, knowledge management, and archives programs and can help you get started. Additionally, the RAC is available as a resource to help you articulate your archival goals and think through strategies to meet them.

Bob Clark is the director of archives at the Rockefeller Archive Center

The views and opinions expressed in individual blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the National Center for Family Philanthropy.