Embracing a More Holistic Approach for Greater Impact

Portion of the cover image for Chicago Beyond's Whole Philanthropy document

In 2015, I stepped away from the field of education and dove into the world of philanthropy.

Previously, I had been principal of Fenger High School on Chicago’s South Side. My experience with funders had been exclusively on the receiving end; my team at Fenger and I worked hard to secure financial resources that would allow us to support our students in a way that could potentially change the trajectory of their lives.

Our school was situated in the Roseland neighborhood, and while it had been deemed hopeless by others in our city and in the media, I encountered the opposite: joy, abundance and the strength of families, neighbors and friends. Still, there were challenges. During my first year at Fenger, there were approximately 300 arrests inside of our school building. We faced a 20 percent dropout rate, and only about a 40 percent state graduation rate.

Despite those statistics, every one of our students and their boundless potential were our North Star. By the time I left Fenger, the stats had changed dramatically. The dropout rate had fallen from 20 percent to 2 percent, attendance and graduation rates had skyrocketed and arrests had dropped from 300 annually to less than 10.

Those changes did not happen because we changed the student population—they happened because we, the adults in the school, began to see things differently. We became more conscious of students’ holistic needs and individual traumas. That consciousness allowed us to become more connected to students—to see them better, and to serve them better.

Fast forward to 2016, when, with the support of philanthropists Mark and Kimbra Walter, I had the opportunity to create and launch a private foundation, Chicago Beyond. My goal was to build on my work at Fenger and ensure that all young people have the opportunity to heal, prosper and live a free and full life. To do that, Chicago Beyond focuses on shifting systems that often create barriers to freedom. We also support hyperlocal, early-stage initiatives that have not previously gained substantial financial and strategic backing.

Philanthropic Blind Spots That Reduce Impact and Harm Relationships

Shortly after the creation of Chicago Beyond, I took a step back to assess our progress. Compared to our aspirations, we had fallen short. Not only were we failing to make the amount of progress I knew that we could, we were also potentially creating more harm and widening inequities. I realized we had fallen into the philanthropic sector’s invisible traps.

During Chicago Beyond’s early days, I participated in meetings with other funders that were steeped in theory and disconnected from reality. The conversations and ideas about “solutions” were far removed from people’s lived experiences and the on-the-ground issues communities face. These discussions were often a stand-in for real action.

Another glaring misstep I recognized early on: We, along with other funders, were leaning into the “Thunderdome” mentality. In other words, we gave resources to whomever did the best job telling the worst story about communities or young people. The process reminded me of fighting for dollars back when I was at Fenger. Even though my Fenger team and I knew what was best for our students, we still had to sell the story. By continuing that pattern when I was on the other side of the equation, investing resources rather than requesting them, my Chicago Beyond team and I were missing out on investing in organizations that had a meaningful impact—even if they weren’t skilled at or didn’t buy into selling a story. We shouldn’t require individuals or communities to recount their traumas to be fully seen by funders.

Another challenge we have grappled with at Chicago Beyond is using deficit-based language. At first, we, along with our peers, were using language that categorized young people as less than, without accounting for their ecosystem and the conditions that may have led us to that assumption. Terms such as “opportunity youth,” “marginalized,” “vulnerable,” and “at-risk,” had placed labels on young people, rather than naming the root of the problem. Language can, intentionally or unintentionally, dehumanize people and reinforce inequitable systems. Using deficit-based terminology created more harm for the very young people we were and are in service of; we were having a negative impact, not a positive one. When we changed our language, we noticed that our relationships with our young people and partners also changed.

These are just a few of the invisible traps in philanthropy, which, if we are not vigilant against, and at the very least notice them, we will fall into them time and time again, and not have the impact we seek.

True Partnership through Whole Philanthropy

At Chicago Beyond, we see a practical alternative to traditional institutional philanthropy that could invigorate the sector’s ability to create deep change. We call our approach “Whole Philanthropy.”

Whole Philanthropy is about re-centering humanness. It is about doing away with the false dichotomy of “us and them.” It’s about recognizing that we are in this together, fighting for and envisioning true freedom for all. This approach requires meaningfully interacting with our partners, not in a paternalistic way, but as equals. Our model forges deep connection with our partners; we seek to build ownership among those we serve, and to tap into the power and expertise of people’s lived experiences.

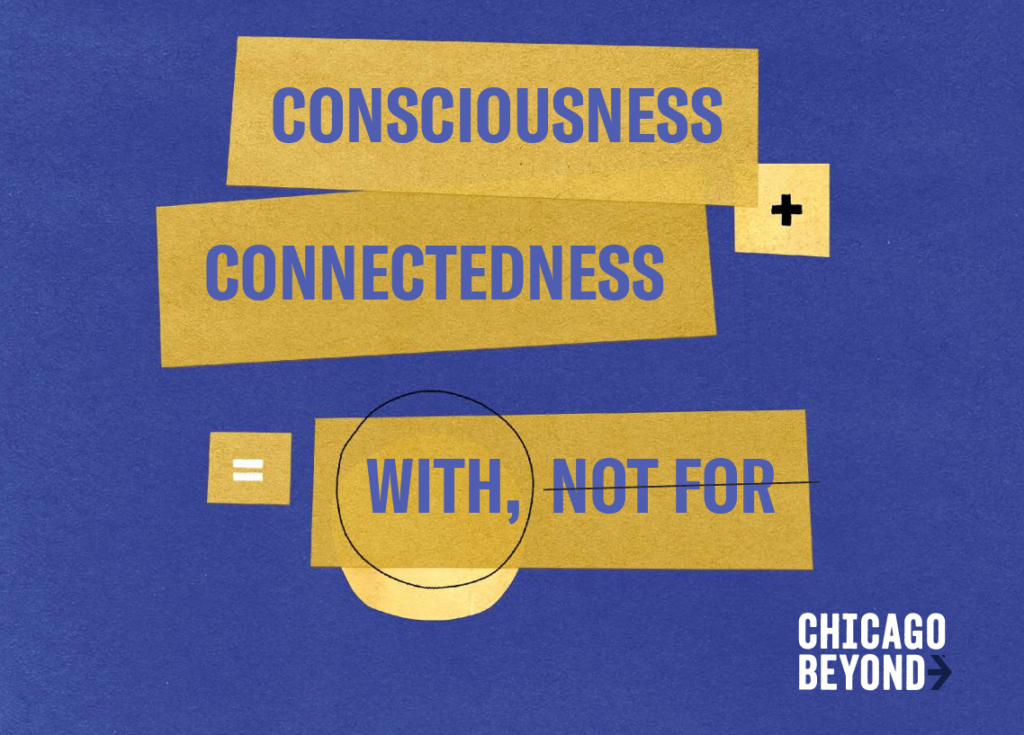

The key to living Whole Philanthropy is our individual orientation to the work. We as funders must see ourselves as actors with power in the systems we are working within—actors that can ultimately upend the very nature of those systems. At Chicago Beyond, our orientation includes three main ideas:

Consciousness: Requires noticing and examining the perceptions, assumptions, and dynamics that inform our individual and organizational beliefs and practices; Being conscious requires us to see differently and bring awareness to our own biases and assumptions as well as our interconnectedness.

+

Connectedness: Requires engaging with all individuals and communities as full and complete, deserving of respect and engagement, as humans.

=

With, not for: Results in us standing in solidarity with our partners.

Whole Philanthropy in Action

As funders, our orientation has implications for who we fund, how we source investments and how we partner.

For example, we know that Black and Brown leaders of smaller, community-driven efforts are often overlooked. This happens for a number of reasons; often, these groups have limited staff to apply for grants and fundraise, have a less formalized organizational structure and have fewer connections to institutional funders and other power brokers. They are overlooked in part because they do not make it onto funders’ radars. When they are noticed by philanthropists, these organizations are often deemed “risky” if they don’t fit traditional funding requirements. To the contrary, these are the people and efforts most primed to move communities forward. Why? Because they are most proximate to their community’s challenges and therefore most accountable and adaptable to community needs. By being more conscious of this dynamic, funders can operate in ways that counter traditional risk assessments.

While it is evident that there is an abundance of Black and Brown leaders shaping community efforts, reaching them calls for deep community ties and trust. One way Chicago Beyond reaches these leaders is through our People’s Assembly, a group of committed Chicagoans who offer ideas, advice and recommendations of individuals doing invaluable block-by-block community work that often goes unnoticed and unfunded. This helps us intentionally address bias and overcome the blind spots of our existing network. By intentionally connecting with community members as equal partners, we open the door to a variety of new ideas that might challenge how we think of existing issues.

Once we partner with an individual or organization, we offer multifaceted support without judgment. While the components of our various partnerships vary based on partners’ unique circumstances, all partnerships start by building real relationships that hinge on trust. Connectedness is the fundamental first step. For other examples of relationship-building, the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project is working to address the inherent power imbalances between foundations and nonprofits.

Critical Questions to Consider

In philanthropy, those in power have the opportunity to work from the inside out. By expanding our consciousness, we as funders can open our eyes to society’s complex, deeply rooted challenges and broaden the set of creative strategies we deploy to address them.

Here are a few questions we as philanthropists should ask ourselves:

- When it comes to sourcing: What is the process our potential partners must go through? Is it burdensome? Who decides which individuals or organizations receive funding?

- When it comes to partnership: Is trust apparent and felt by all individuals involved in our partnerships? How do we know? Beyond a financial investment, how do we support partners? How can we better understand their stories and their environment?

- When it comes to narratives: What harmful narratives might we be pushing? How are we using deficit-based language and how can we shift to more empowering storytelling?

- When it comes to power: Am I reinforcing imbalanced power dynamics? How can I shift power in ways big and small? Am I, intentionally or unintentionally, reinforcing power dynamics that is getting in the way of impact?

- When it comes to impact: What are the questions we’re trying to answer or needs we’re aiming to meet? How is success defined? Whose expertise is valued? Are we seeking to evaluate community organizations or to evaluate ourselves? Are we continually assessing how we can best support the communities we serve?

These questions, while crucial, are not a checklist. They are a compass, and we grapple with them often at Chicago Beyond. Simply noticing philanthropy’s missteps will not change how philanthropy operates. Only when we—the individuals who make up philanthropy—shift our orientation will we see the field transform. Once we lean into consciousness and connectedness in all aspects of our work and create a funding environment that is joyful and abundant, we’ll ensure that everyone has a chance to thrive.

Liz Dozier is the Founder & CEO of Chicago Beyond

The views and opinions expressed in individual blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the National Center for Family Philanthropy.