Transparency Case Study: The Russell Family Foundation

swimming pool with decorative stones

Editor’s Note: What choices do family foundations and funds have when it comes to transparency? And what approaches do other families take when it comes to managing transparency, communications, and privacy? NCFP’s new guide, Transparency in Family Philanthropy: Opening to the Possibilities, examines how family funders are thinking, acting—and, in some cases, not acting—when it comes to how open and accessible they are with others. Opening to the Possibilities features a collection of five diverse funder stories exploring different takes on how families think about and act on transparency—and what they have learned as a result. This month we share the experiences and lessons learned from The Russell Family Foundation.

Approach

“When we started thinking about transparency, it was when we were looking at ways to help communities develop and how they could become more resilient, flexible, and intuitive in their own ways,” says Richard Russell, board member of The Russell Family Foundation (TRFF). “We looked at what was making a difference in the waters of Puget Sound. What we learned was that more than 50 percent of the pollution of Puget Sound comes from the communities surrounding it, and that those communities have a lack of consciousness that they live next to this incredible fjord and are dumping everything in there.”

“We asked ourselves: what is our theory of change? What will make a difference down the road?” says Russell. “We saw an opportunity to build trust and convene community. The more we can be open with each other, the better the quality of our connection.”

One of the ways to be open is to share mistakes, he says. “In our culture, mistakes are taboo. Yet revealing mistakes can be a source of strength,” he says. “We all think we have to protect ourselves. Yet a lot of our nervousness or fears around that are misguided.”

“My parents (George and Jane Russell, founders of TRFF) believed that you can advance progress so much faster if you got the right people in the room and got out of their way. If you try to keep people out of the room or hide mistakes that people are inevitably going to make, it injects more tension into relationships,” says Russell.

In the spirit of its founders, TRFF posts its mistakes publicly. In fact, for years, one of the most popular videos it ever posted was on a failed program related investment that it had made to a nonprofit. “The video featured interviews with the executive director of the nonprofit, interviews with me from TRFF, what we had learned, and how we the foundation processed these lessons learned across the silos,” says CEO Richard Woo.

“People don’t learn from each other if they aren’t open,” says Russell. “One of the most valuable things we’ve been able to do as a community leader is to convene people on issues that they aren’t talking about—to get people to let their hair down and talk openly. We all need to be a learning organization.”

What’s Working

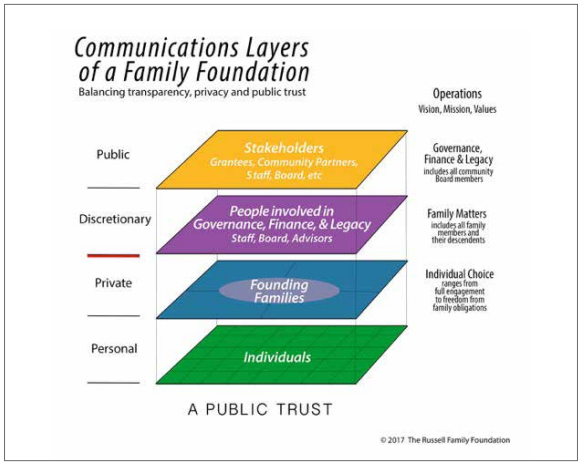

Richard Russell and several board members of TRFF developed a framework that looks at the multiple layers of a family foundation enterprise. They use this as a tool—modeled after a multidimensional chessboard—to help them understand the layers of responsibilities and expectations they face in how they communicate, and with whom, every day.

The model has four levels: individuals; founding families; staff, board and advisors (people involved in governance, finance and legacy); and stakeholders (grantees, community partners, etc.).

“The ones we pay most attention to in transparency discussions tend to be the top and bottom: how we communicate with the community and public, and how we communicate interpersonally. Yet there are multiple layers between that—how transparent we are with board members who are not family, staff, grantees, etc.,” says Woo.

“This tool helps us initiate conversation about important issues, which might be difficult to surface otherwise. It illuminates areas where different types of communications are appropriate, and where boundaries may exist,” says Woo.

For example, “Sometimes we do investments that aren’t exactly secret but it’s not known yet,” says Russell. “There are times when telling everything that’s going on isn’t the right approach, and we have to discern what is right to share, and when. Sometimes a little quiet is important to the success of a venture.”

“There are times when we may want to strategically remain quiet, to encourage and allow different rates of uptake with what we’re going to say. In other words, allow the recipe to fully cook,” says Woo. “It’s been helpful for us to use this tool to ask ourselves: when is the time for us to be fully transparent? And when is it time to conduct conversations below the radar for strategy’s sake?”

Lessons Learned

“The kinds of changes foundations want to make are not going to happen from technical solutions. We can’t just throw money at a problem because there’s not enough money. These dilemmas require human will and community will to put into place necessary changes,” says Woo. “We think of our grantmaking in that way. We want to transform the dilemmas we are trying to address, and transform the nature of relationship between grantor and grantee.”

This can’t be done without thoughtful attention to transparency. “Transparency relates to the question of transaction versus transformation. These are core questions in the field. There are givers and receivers, those who have and those who don’t. The obstacles around transparency lock in place some of those divisions,” says Woo.

According to Russell, “As a field, the people who are philanthropists giving away money have a big series of grantee assumptions to overcome. There is a long-standing habit of philanthropy not being transparent, and we have to work through that resistance,” says Russell. “The community is right to wonder.”

“We had heard rumors that some will use honesty and transparency against us. Yet what we’ve found is that it has brought about a much more cohesive sense of community. It has put us much more on the same side of grantees,” says Russell.

“Hopefully we have allayed their fears.”

Philanthropy has been so reluctant to share its failures with other funders and the broader community. It would go a long way toward building trust if we did. We learn the most when we do things wrong. —Pamela David, (Formerly) Walter & Elise Haas Fund