How to Interrupt the “Vicious Cycle of Inherited Wealth:” A Conversation with Iris Brilliant

For wealth inheritors, having access to a large sum of money they did not earn is a privilege, but often comes with mixed emotions and a deep sense of responsibility. Acknowledging and building a healthy and transparent relationship to wealth can help improve personal and family relationships, deepen connections in community, and ultimately promote greater, and more equitable redistribution of philanthropic dollars. NCFP Program Manager Britt Benavidez sat down with Iris Brilliant to learn more about her experiences and recommendations for next generation philanthropists. Brilliant leans on her own experiences as a wealth inheritor to coach other inheritors to develop a healthier relationship to wealth and break out of the “vicious cycle of inherited wealth.”

Can you tell me more about yourself and how you got into this coaching role?

I’m from the Bay Area in California and I’m the first person in my family lineage to really grow up wealthy. When I was first introduced to institutional philanthropy, I felt such a strong disconnect in those spaces because I noticed the loud absence of the communities that these institutions were funding and how all decisions were being made for other people behind closed doors. I started to put language to that discomfort. Once I inherited wealth, right after college, I realized I needed to put my money where my mouth is and begin to discover what it means to really align my wealth with my social justice values. I began to support wealthy people to take more courageous steps with their money, and to find more peace within themselves.

What are some of the challenges that you’re seeing these wealth inheritors face?

Most of my clientele are inheritors with social justice values. They often grapple with wanting material comforts while knowing they did not contribute to earning their wealth. This knowledge that they have inherited wealth that was not created by their own skills, talent, or effort often creates a deep insecurity.

They also have challenges in how they relate to their careers, especially if they have inherited enough money to not need to work. Many inheritors wait around for the perfect job and get stuck in this hamster wheel of waiting and overthinking, all the while not developing any work-related skills, and then becoming fundamentally disconnected from the rest of society and dissatisfied in their lives.

Many inheritors also struggle with a fear that others will exploit them for their wealth. Some are just friends with other wealthy people to ease that fear. Many fall in love with people who aren’t wealthy, but then must confront the incredibly uncomfortable stuff that comes up when you tell someone else that you have a trust fund or that you’ve inherited millions of dollars.

All of these challenges can lead to people feeling stuck and inadequate. It especially makes it harder to understand, “Why am I feeling depressed or anxious when I’ve had such a good life when I’ve been raised with so much privilege?”

How do you define a healthy relationship to wealth?

I think a healthy relationship to wealth is an open hand. Your job is to keep the money moving. Edgar Villanueva teaches us that in his book Decolonizing Wealth that still water gets stagnant, allowing bacteria to grow in it, and then nobody can drink from it. So a healthy relationship to wealth is to keep it moving, not get attached to it, and instead to support it flowing to where it wants to flow.

Iris notes that wealth inheritors can feel significant pressure to fill the shoes of the wealth creators. Here’s Iris trying to fill some big shoes!

What are the ways that that wealth can or does interfere with family relationships?

When your parents are your source of money, it introduces an aspect of power in the relationship, whether or not that was the intention of the parents. It makes it hard for inheritors to figure out what type of relationship they want to have with their family of origin and to find their own footing. There’s also so much pressure that comes when your parents have been incredibly successful, even if your parents aren’t directly pressuring you.

The weight of those expectations, the fear of betraying your family by not being a good steward of the wealth, can live in the body. And the more money and power and status you’re inheriting, the more pressure there is.

What are ways that people can rethink their family legacy if they have a formal family philanthropy or not?

Many of the default legacy messages are often about that unconscious drive to preserve power and status in the family lineage. We often start with an intention of wanting to instill philanthropic values in our children. As philanthropies grow in influence and scale, I’ve seen many of them unintentionally orientate themselves around status and power.

I encourage people who have decision-making power in family foundations to really ask yourselves, “What is this really for?” If part of your desire is to use a family foundation to feel close with your kids, ask yourself is this really the only way that you could do that? If you want to teach your kids to be generous people, that’s beautiful. However, keeping 95% of the assets of a foundation locked away in investments is not modeling generosity; it’s modeling wealth accumulation. There’s a lot of different ways to teach our kids to be philanthropic and generous. For example, you can model philanthropy by deciding to sunset a foundation. That models a willingness to move all of your financial resources into the world, and to let go of the status and the social capital that we gain when we have a foundation in our family name.

You’ve identified a framework that illustrates the “vicious cycle of wealth”. Tell me more about this framework, and what are your recommendations for breaking out of the vicious cycle?

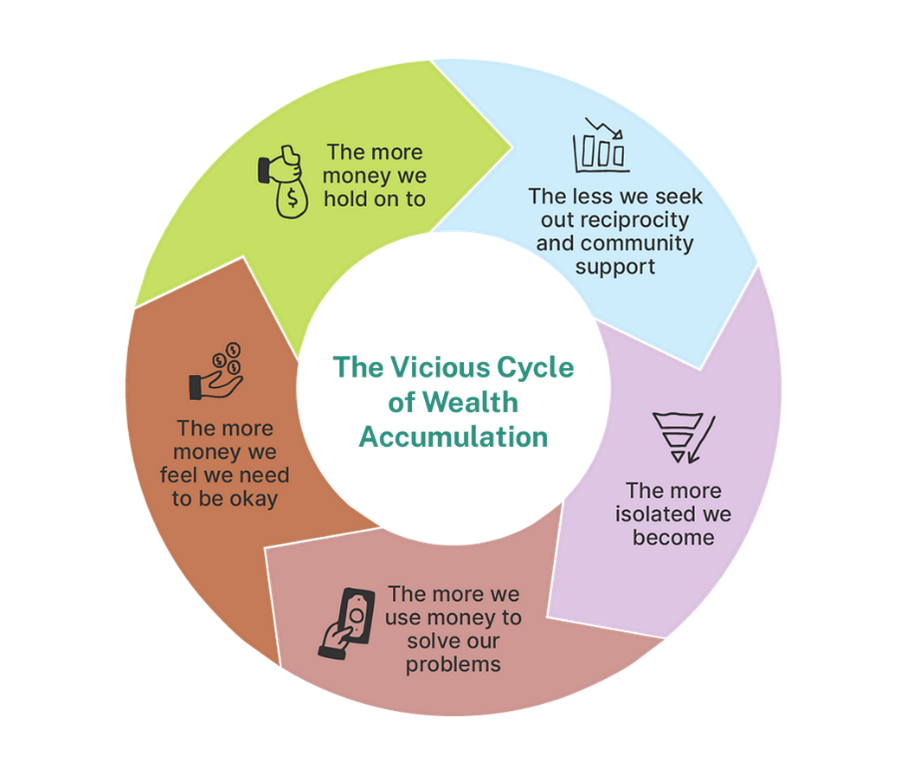

The vicious cycle of wealth accumulation depicts how the more money we hold onto, the less we seek out reciprocity and community support, the more isolated we become, the more we use money to solve our problems, and then therefore, the more money we feel we need to be okay.

The Vicious Cycle of Wealth Accumulation, courtesy of Iris Brilliant

The first way to break the cycle is to develop a sense of self-trust, and this really means to know yourself, to figure out what integrity looks like and means to you, and what are the values that you want to abide by in your life so that you can be someone that you trust.

The second is to be a good community member, to be generous with the people that you love, not just financially, but with your time and your efforts to really invest in your relationships, to show up even when it’s inconvenient. That is one of the biggest ways we can create safety and security in our lives because you’re telling people through your actions that you are invested in them and that naturally invites them to be invested in you.

Next is to practice receiving. Many of us struggle with asking for and receiving help. It’s just much more comfortable to use money to get what we need, so dare to find ways of receiving, accepting support without paying people to do that.

The fourth is essentially to find work that you can live off of and that is tangible, meaningful, and something you can imagine doing for a long time. It doesn’t have to be perfect, but knowing that you have work that you can always lean on if your money were to disappear tomorrow builds confidence.

The last one is adaptability, resilience, and resourcefulness. I crammed three into one. It involves developing the understanding of how not to use money to get out of problems or as a buffer.

What is your vision for family philanthropy?

Iris Brilliant:

There’s $264 billion in family foundations. That wealth came from the world, and I want to see that money return to the world to meet this moment of unprecedented climate catastrophe and economic precarity. I also want people to get to experience the joy and liberation of letting go of control and of getting unstuck.

*Interview edited for brevity and clarity. Read more from Iris here and get in touch with her here.

The views and opinions expressed in individual blog posts are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the National Center for Family Philanthropy.